China Self-Driving Along the Sino-Myanmar Road (The Burma Road) – Day 6: From Wanding to Lashio

On the sixth day, I entered Myanmar and continued south along the Sino-Myanmar Road. After crossing three mountain ridges and driving 185 kilometers, I arrived at the endpoint of the Sino-Myanmar Road: Lashio (腊戍). At this point, I had followed the wartime route and completed the entire journey along the Sino-Myanmar Road.

The Final Stretch: From Wanding to Lashio

Upon reaching Wanding (畹町), I found that there was just a small remaining segment of the 1,100-kilometer journey, under 200 kilometers. However, even this short distance presented significant challenges.

The Process of Entering Myanmar

Before leaving Beijing, I reached out to three companies that claimed to handle the entry procedures. The first company started with strong assurances, but then became unresponsive. The second company was vague, neither confirming nor denying their ability to help. The most confusing was the third company, which provided inconsistent and often contradictory information every time I contacted them. With no clear answers, I decided to take things one step at a time.

At the Wanding Border Crossing

At the Wanding (畹町) border crossing, I inquired about the possibility of driving into Myanmar. I was told to visit the Foreign Affairs Department at the Ruili (瑞丽) Public Security Bureau to complete the necessary paperwork. Therefore, I left Wanding and drove toward Ruili.

The journey from Wanding to Ruili was nearly 30 kilometers. The first part of the route took me along a small road parallel to the border, surrounded by dense vegetation, with no signs of human presence.

The Wanding River (畹町河) along the roadside still flows gently, with several stretches so narrow that one could easily leap across and cross the border.

After more than 10 kilometers, the Wanding River (畹町河) flows into the Ruili River (瑞丽江), where there is a ferry crossing. However, vehicles cannot pass; the only option is to head north on National Highway 320 (320国道). Near the ferry, in the bushes, there is a faintly visible monument, which turns out to be a boundary marker (界碑).

After crossing the Ruili River (瑞丽江), the road becomes flat and soon leads into the city of Ruili (瑞丽), where I headed straight to the Public Security Bureau. I was informed that I first needed to obtain a border pass, which required documents such as a temporary residence permit, company business license, and others. Only after completing these procedures could I address the issue of bringing the car into Myanmar. Moreover, even if all these procedures were completed, I could only operate within the border area. As for my Myanmar visa, it was valid only for air entry points, not land borders.

With no other option, I decided to stay in Ruili (瑞丽) and began inquiring around. Eventually, I found a company on the Myanmar side that could assist with the paperwork, though it would take about 8 to 10 days.

In recent years, when people mention Myanmar, many are filled with fear. However, my unwavering determination to go and the outcome that followed made me extremely satisfied. First, my interest played a part—taking the time to complete the entry procedures, despite the long wait and significant cost, was worth it for me to travel the entire Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路).

Second, luck was on my side—I wasn’t targeted by criminal groups.

Third, my low reliance on my phone helped. I don’t answer unfamiliar numbers, rarely download apps, and avoid any form of bundling or registration.

During my days waiting in Ruili (瑞丽), I spent time exploring the area, particularly visiting Nong Island (弄岛) near Lei Yun (雷允), where I carefully searched the site of the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Factory from the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression. Later, I drove north along the Nu River (怒江) and made a trip to Bingchacha (丙察察).

Finally, the approval was processed, and I rushed back to Ruili (瑞丽) as quickly as possible. The Ruili border crossing (瑞丽口岸) is located 5 kilometers south of the city center, called Jie’gao (姐告). When I arrived at the crossing as scheduled, the Myanmar officials were already waiting for me. In less than 20 minutes, I smoothly crossed the border and entered Myanmar.

After entering Myanmar, I headed straight to Jiugu (九谷).

The area I entered was called Muse (木姐). My goal was the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路), but the road itself had nothing to do with Muse. So, without wasting any time, I immediately headed for Jiugu, 30 kilometers away. Jiugu is a small village located directly across from the Wanding (畹町) border crossing. The old Sino-Myanmar Road used to run from Wanding, crossing the border to reach Jiugu.

A few days ago, I had stood in Wanding, looking south toward Jiugu, essentially standing in China and gazing into Myanmar.

Now, I stand in Jiugu (九谷), looking north toward Wanding (畹町)—standing in Myanmar and gazing into China.

At the end of Jiugu Village (九谷村), I turned around and saw the Heishan Gate (黑山门) behind Wanding (畹町), fully visible like a giant screen. To the east, at a lower elevation, is the mountain pass where the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路) crosses the mountain. This is the location where, in 1944, the Chinese Expeditionary Force fought its final battle against the Japanese army on Chinese soil, after advancing from Longling (龙陵).

Following this battle, the Japanese army retreated into Myanmar and continued their resistance, utilizing fortifications they had previously constructed in Jiugu (九谷). With the assistance of the U.S. Air Force, the Chinese Expeditionary Force launched a direct assault, flanking maneuvers, and surrounding attacks, eventually breaking through the Japanese defensive lines.

Meeting at Mangyou and the Stilwell Road

Leaving Jiugu (九谷), I continued along the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路). After passing through several small villages, I arrived at Mangyou (芒友). On January 27, 1945, a meeting ceremony was held here between the Chinese Expeditionary Force, the Chinese troops stationed in India, and the U.S. military.

Mangyou is a junction, with the road to the west leading to Muse (木姐), which I had just crossed into, and further west from Muse is Nankan (南坎). In fact, the road from Mangyou to Nankan is the China-India Road, also known as the Stilwell Road (史迪威公路). According to Mr. Ge Shuya (戈叔亚), a special long American military engineer bridge still stands in the outskirts of Nankan.

From Mangyou (芒友) to Lashio (腊戍), I crossed three mountain ranges.

The road south from Mangyou is part of the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路). Along this path, I crossed three mountain ridges. The first mountain was the most challenging, taking over half an hour to ascend and descend. Along the way, there were very few villages.

After crossing the first mountain, I entered a valley where a larger town, called Nanbaga (南巴加), is located. On the streets, I noticed that local students were all dressed in white on top and green on the bottom. Later, as I traveled through much of Myanmar, I realized that this seemed to be the standard uniform for students across the country.

After crossing the valley, I ascended the second mountain. This one was lower than the previous one, and it took less than an hour to cross.

After descending the mountain, I entered another valley, where the town of Guguai (古盖) was located.

Guguai town had many restaurants, where passing vehicles would typically stop to rest, have a drink, or grab a bite to eat. There were two main types of meals offered: one was boiled rice noodles, and the other was a buffet-style meal.

The boiled rice noodles cost 1,000 kyats, while the buffet-style meal was priced at 3,500 kyats for the cheaper option and 4,500 kyats for the more expensive one. When I entered Myanmar, I exchanged 5,000 RMB for 950,000 kyats in Muse (木姐). This means that the 3,500 kyat buffet was roughly equivalent to just over 18 RMB.

Probably influenced by the British, coffee is available everywhere in Myanmar, priced between 300 and 500 kyats, which is roughly 1.5 to 2.6 RMB. While cheap, based on my taste, it was quite unpleasant. Rather than being coffee, it felt more like sugary water.

After resting in Guguai (古盖), I continued my journey. In a place called Xingwei (兴威), I passed an intersection and checked the map, which indicated that heading east would lead to the Hupan (霍班) direction. This meant that from this intersection, one could reach the territory of the De’ang people (德昂人).

In fact, between Guguai and Xingwei, I saw several groups of fully armed government soldiers. I had heard that the De’ang people have their own armed forces and often block roads to extort money from passing vehicles. However, when the government troops arrive, they quickly retreat.

Myanmar has many toll booths, located every few dozen kilometers, each charging 500 kyats, which is about 2.6 RMB. What puzzled me was that at each toll booth, there was a person sitting inside, recording the license plate numbers of passing vehicles with paper and pen.

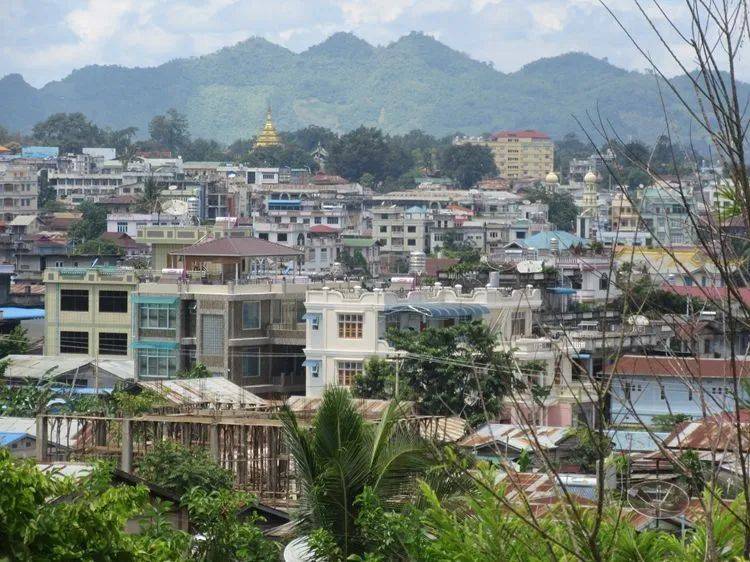

After passing Xingwei (兴威), I descended into a large valley, vast and expansive—this was Lashio (腊戍), the endpoint of the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路). According to the information, the total length of the Sino-Myanmar Road is 1,153 kilometers. My actual driving distance from Kunming (昆明) to Lashio (腊戍) was 1,127 kilometers.

Upon reaching the outskirts of the city, I noticed an airport on the right side. After the Chinese army entered Myanmar, Chiang Kai-shek (蒋介石) had flown to Lashio (腊戍) for an inspection and coordination.

As I passed by, a propeller-driven passenger plane was landing, similar to our Y-7 (运七) aircraft. In front of the airport, a large crowd had gathered—most of them men dressed in “longyi” (隆基) and flip-flops, seemingly there to greet the arriving flight.

Finally, I reached the endpoint of the Sino-Myanmar Road.

Passing the airport, there were a few courtyards along the roadside, likely military barracks. Soon after, a line of military trucks appeared ahead. Seeing this scene, I felt a surge of emotion. During the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, our military trucks would have looked similar, forming long lines as they made their way from Yunnan (云南) to here.

I followed the military trucks for about one or two kilometers, and then the train station appeared. It was the Lashio (腊戍) Railway Station, the terminus of the Myanmar Central Railway in the northeastern part of Myanmar.

During the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, supplies shipped from the United States were transported by train from Yangon (仰光) to Lashio (腊戍), and then by truck along the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路) into China. It was precisely because of this “lifeline” that the Chinese army received the necessary equipment to resist the Japanese forces.

The train station appeared very old-fashioned, with even the water refilling station for the steam locomotives still intact. The timetable in the waiting room showed that there was one train running daily between Lashio (腊戍) and Mandalay (曼德勒). Seeing the tracks overgrown with weeds, I couldn’t help but wonder if the trains were still running. However, during the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, this station was quite busy.

Transporting goods over a distance of over a thousand kilometers with trucks carrying only 3 tons of cargo was highly inefficient, much like the later Hump Airlift (驼峰航线). It was a costly and unprofitable method of transport. Yet, for the sake of a free China, this price had to be paid, with no other option except surrendering to Japan.

Standing at Lashio (腊戍) Railway Station, I was deeply moved. Three weeks ago, I had set off from Panjiawan (潘家湾) in Kunming (昆明). Now, I had finally reached the endpoint of this road. I can proudly say that using Professor Zeng Zhaolun’s 1941 “Diary of the Borderlands” (《缅边日记》) as my guidebook, I strictly followed the entire Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路) from start to finish. Thousands of photos and hundreds of minutes of video will remain treasures I cherish forever. The purpose of this journey wasn’t to seek personal satisfaction through boasting or to challenge myself with a long solo ride. I simply wanted to witness firsthand a piece of history that has yet to fully be understood.

7 Days GolfingTour

7 Days GolfingTour

8 Days Group Tour

8 Days Group Tour

8 Days Yunnan Tour

8 Days Yunnan Tour

7 Days Shangri La Hiking

7 Days Shangri La Hiking

11 Days Yunnan Tour

11 Days Yunnan Tour

6 Days Yuanyang Terraces

6 Days Yuanyang Terraces

11 Days Yunnan Tour

11 Days Yunnan Tour

8 Days South Yunnan

8 Days South Yunnan

7 Days Tea Tour

7 Days Tea Tour

8 Days Muslim Tour

8 Days Muslim Tour

12 Days Self-Driving

12 Days Self-Driving

4 Days Haba Climbing

4 Days Haba Climbing

Tiger Leaping Gorge

Tiger Leaping Gorge

Stone Forest

Stone Forest

Yunnan-Tibet

Yunnan-Tibet

Hani Rice Terraces

Hani Rice Terraces

Kunming

Kunming

Lijiang

Lijiang

Shangri-la

Shangri-la

Dali

Dali

XishuangBanna

XishuangBanna

Honghe

Honghe

Kunming

Kunming

Lijiang

Lijiang

Shangri-la

Shangri-la

Yuanyang Rice Terraces

Yuanyang Rice Terraces

Nujiang

Nujiang

XishuangBanna

XishuangBanna

Spring City Golf

Spring City Golf

Snow Mountain Golf

Snow Mountain Golf

Stone Mountain Golf

Stone Mountain Golf