China Self-Driving Tour Along the Sino-Myanmar Road – Day 4: From Baoshan to Longling

I believe the stretch of the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路) between Baoshan (保山) and Longling (龙陵) is the most exciting part of the journey. Not only because the scenery along the way is beautiful, but also because this route is home to significant historical landmarks, such as the Huitong Bridge (惠通桥), which played a crucial role in resisting the Japanese advance, and Songshan (松山), where the Chinese Expeditionary Force endured great hardship. The events depicted in works like My Battalion Commander, My Battalion (我的团长我的团) and West Yunnan 1944 (滇西1944) took place in this area.

The route from Baoshan (保山) to Longling (龙陵) includes the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路), the Hangrui Expressway (杭瑞高速公路), and National Highway 320 (320国道). The expressway and the national highway are not far apart, with the national highway covering about 108 kilometers. The Sino-Myanmar Road is farther from the other two, passing through Shuchang Township (水长乡), Huitong Bridge (惠通桥), and Songshan (松山). According to Professor Zeng’s 1941 record, the distance was 169.8 kilometers, but in 2015, my driving distance was 158 kilometers.

First Segment: From Baoshan to Shuchang Township

Leaving the city of Baoshan (保山), the area remains densely populated, with villages along National Highway 320 (320国道) connected one after another. After 8 kilometers, I passed through the Baoshan Valley (保山坝子) and began ascending. Soon after, I arrived at Daguanshi Village(大官市村), which sits at an elevation of 1,930 meters, 270 meters higher than Baoshan Valley.

After Daguanshi Village (大官市村), there is an intersection. To the right is National Highway 320 (320国道), and to the left is Provincial Road 229 (now seemingly renamed as National Highway 555, 555国道). Provincial Road 229 leads to Shidian County (施甸县), and the 18 kilometers from this intersection to Shuchang Township (水长乡) was once part of the old Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路).

As I entered Provincial Road 229 (229省道), the road descended steadily. On both sides of the road, the hillsides were covered in dense pine trees, creating a lush, green landscape. The highway winds through the forest, offering a refreshing and picturesque view, evoking a sense of peace and beauty.

After descending for 16 kilometers, I entered a valley, and soon a village appeared. Along the roadside, there was a prominent sign reading “707,” indicating that the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路) from Kunming (昆明) to this point is 707 kilometers. Along this stretch of road, there are also signs marked “808,” signifying another key milestone.

Second Segment: From Shuchang Township(水长乡) to Yangyuping(羊芋坪)

After passing “707,” I continued toward Shuchang Township (水长乡), where the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路) changes to County Road 191 (191县道). This county road stretches from Shuchang Township all the way to the National Highway 320 (320国道) near Longling (龙陵), covering a total distance of 102 kilometers. The famous Huitong Bridge (惠通桥) and Songshan (松山) are both located along this route.

Leaving Shuchang Township (水长乡), I immediately began ascending the mountain. After 6 kilometers, I reached the first mountain peak, where a village called Jiangyizhai (姜邑寨) is located, at an elevation 217 meters higher than Shuchang Township. Over the next 5 kilometers, I passed through several villages, including Shenjiafen (沈家坟), Ganshuigou (甘水沟), and Lishantou (李山头). Among this series of villages, the most picturesque was Yangyuping (羊芋坪), situated on the mountainside with a well-arranged, scattered layout.

When the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路) was first constructed in early 1938, the primary goal was to ensure it was passable, with plans to gradually improve the road quality over time. As a result, some sections of the road are quite steep, with straight slopes often around 15%, and in some curves, the incline can even reach 30%. When converted to angle, this is roughly just over 16 degrees.

Third Segment: From Yangyuping to Huitong Bridge

After 15.1 kilometers from Yangyuping (羊芋坪), I reached an intersection. Turning left, there was a narrow road, with a sign indicating “Da Fengziwo Fort” (大蜂子窝碉堡). Although the road was narrow, the surface was relatively smooth and easy to drive on. Following it for 8.5 kilometers, I reached Xiaxinzhai (下新寨), and then walked for less than an hour to reach a mountain pass where remnants of the Chinese Expeditionary Force’s fortifications from the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression still stand.

From 1942, when the Japanese army arrived at the Nu River (怒江), to the 1944 counteroffensive in western Yunnan (滇西), Chinese and Japanese forces faced off here for two years. Along the Nu River, many fortifications were built, and Da Fengziwo was just one of them.

I retraced my steps back to County Road 191 (191县道) and continued for another 2 kilometers, passing by Lao Lutian (老鲁田) and Yiqiu Tian (一丘田). In May 1944, when the Chinese Expeditionary Force crossed the Nu River (怒江) to attack the Japanese forces in western Yunnan (滇西), artillery positions were set up here, with the target being Songshan (松山) on the opposite bank of the river.

Standing at the mountain top, far below, I could clearly see the Nu River (怒江) winding through the valley, with the Huitong Bridge (惠通桥) spanning across it, as well as the current highway bridge in use today.

At eye level across from me was a small hill that seemed rather unimpressive—it was Songshan (松山). From this angle, Songshan appeared almost insignificant, but its background was anything but. That background was Gaoligong (高黎贡), which Songshan is part of. The first time I encountered the name Gaoligong, I mistakenly thought it referred to a mountain abroad. In fact, it’s a transliteration from the Jingpo language, meaning “the mountain of the Gaoli family.”

Gaoligong is the westernmost range of the Hengduan Mountains (横断山脉), running north to south. The northern section is located in Tibet, where it’s called Boshula Pass (伯舒拉岭). If you’re traveling the Sichuan-Tibet Highway (川藏公路), you’ll have to cross it. As you move southward, the mountains become shorter, and between Gaoligong and the Nu River (怒江), lies the valley carved by the river itself.

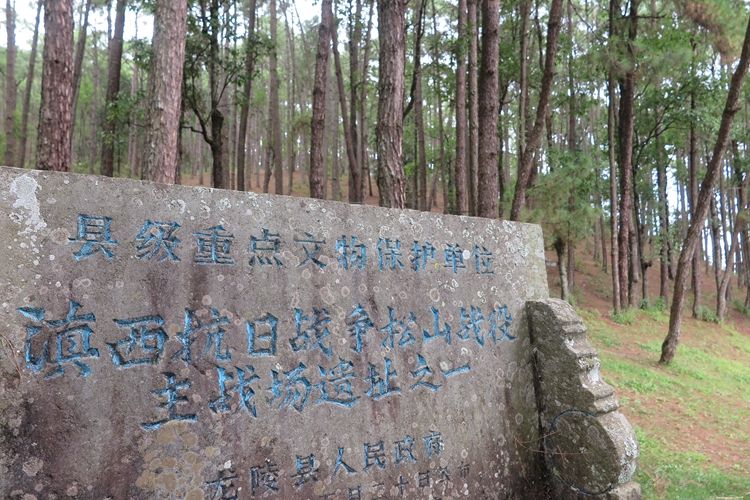

Although Songshan (松山) is not very large, the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路) curves around it after crossing the Nu River (怒江), almost forming a complete loop. In other words, Songshan stands high above, strategically controlling the road. During the two years that the Japanese army occupied western Yunnan (滇西), they constructed numerous military fortifications on Songshan with the aim of completely severing the Sino-Myanmar Road.

Leaving the artillery position site, I descended the mountain and arrived at Huitong Bridge (惠通桥). The downhill route stretched 19 kilometers, with the elevation dropping from 1,534 meters to 738 meters. The entire road was paved with stone, and some refer to it as the Shitang Road (石塘路). I had encountered several such roads since Yangbi (漾濞), with the longest section being on both sides of Huitong Bridge.

During the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression, the initial construction of the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路) involved stone paving. Later, to improve transportation efficiency, asphalt was imported from abroad. However, before it could be fully laid, the Japanese army arrived, and they ended up benefiting from this effort.

Huitong Bridge (惠通桥) dates back to the Qing Dynasty (清朝), and during the Republic of China period, it was rebuilt using more advanced construction materials, with funding from the overseas Chinese philanthropist Mr. Liang Jinshan (梁金山). Shortly after its completion, the war broke out. When the Sino-Myanmar Road was being constructed, the bridge was rebuilt again to accommodate vehicles. On May 5, 1942, as the Japanese forces advanced to this area, the Chinese army blew up the bridge. It was repaired during the 1944 counteroffensive in western Yunnan (滇西).

Some articles mention that the Chinese army’s timely destruction of Huitong Bridge (惠通桥) blocked the Japanese forces on the west bank of the Nu River (怒江). In reality, by that time, the Japanese forces had already crossed the river. What truly stopped them were the hurriedly deployed 36th Division and the bombing raids by the Flying Tigers (飞虎队).

While in Kunming (昆明), I often heard stories about the Flying Tigers and saw remnants of their presence. This volunteer force, once stationed in Kunming, effectively stopped the Japanese aircraft that had been wreaking havoc on the city, ensuring they no longer dared to come back. Mr. Ge Shuya (戈叔亚) told me that many of the older residents of Kunming still hold the Flying Tigers in high regard. This reminds me of the towns of Carentan in Normandy, France, and Bastogne in Belgium. The former still raises both the Stars and Stripes and the French flag side by side, while the latter has erected numerous memorials for the American soldiers who sacrificed their lives for them.

The Nu River (怒江) region is home to three famous ancient bridges: Huitong Bridge (惠通桥), the southernmost of the three, and to the north, there are Huiren Bridge (惠人桥) and Shuanghong Bridge (双虹桥). The straight-line distance between Shuanghong Bridge and Huitong Bridge is about 63 kilometers. All three bridges are still standing, with Shuanghong Bridge still accessible to motorcycles and pedestrians, while Huiren Bridge only has its bridge piers remaining.

Fourth Segment: From Huitong Bridge to Songshan

After crossing Huitong Bridge (惠通桥), the road begins to ascend. Continuing upward, I reached a larger town called Lamen (腊勐). The Japanese forces stationed at Songshan (松山) named their garrison the Lamen Guard Unit (拉孟守备队), which was directly linked to this town.

After Lamen (腊勐), I reached Daya Kou Village (大垭口村), located on the western side of Songshan (松山). In 1942, when the Japanese forces advanced from Myanmar (缅甸) to this area, they discovered that the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路) curved around Songshan, almost forming a complete loop. As a result, they constructed fortifications on Songshan in an attempt to control and block the Sino-Myanmar Road.

By June 1944, when the Chinese Expeditionary Force launched an attack on Songshan (松山), the skies were under the control of American planes, which regularly dropped bombs on Songshan. On the ground, 150 heavy artillery pieces were deployed, and with the support of American-supplied shells, they relentlessly pounded the mountain, almost turning the entire area upside down. However, when the 71st Division (71军) charged forward, they were met with a barrage of bullets— the Japanese fortifications were still intact.

Due to the heavy casualties suffered by the 71st Division, the 8th Army (第8军) took over the assault. After 95 days of fierce fighting, with a total of 7,763 casualties, Songshan was finally captured on September 7th.

In the Battle of Songshan (松山), the Chinese side deployed a total of 20,000 soldiers, while the Japanese forces numbered only 1,300. These soldiers were from the 113th Regiment of the 56th Division. Despite being surrounded on all sides and cut off from reinforcements, the 1,300 Japanese soldiers managed to hold their ground at Songshan for three months. In the end, only 15 were captured, 35 managed to escape, and the remaining 1,250 were all killed by the Chinese forces.

Some online articles describing the Battle of Songshan (松山) suggest that, after prolonged assaults, the Chinese forces resorted to digging tunnels, eventually reaching beneath the main Japanese stronghold and planting several tons of explosives, blowing the mountaintop apart, which led to a resounding victory. However, the reality is that by the time the explosion occurred, the Japanese soldiers had already evacuated from the main stronghold.

If you visit Songshan today, you’ll see that the mountain is riddled with various individual trenches, machine gun positions, and interconnected communication tunnels, all carefully camouflaged. These defensive structures are spread across the mountain, and unless you get up close, it’s nearly impossible to detect them. The Japanese forces, dispersed across the area, made every step forward for the Chinese army come at a high cost. After the main stronghold was destroyed, the battle continued for another 18 days before the victory was finally secured.

The ferocity of the Battle of Songshan (松山战役) is something that people today can hardly imagine. I once walked through every position on Songshan with a copy of Mr. Yu Ge’s (余戈) work in hand. As a Chinese, I deeply admire the heroes of the Chinese army who gave their lives here during the war of resistance. However, at the same time, I can’t help but sigh when I think about the meticulously constructed Japanese positions and their resilience. The scale of their fortifications and their stubborn defense serve as a testament to their determination, making the victory all the more bittersweet.

The positions built by the Japanese forces were incredibly detailed. Layer upon layer of defenses supported one another, with fully equipped facilities. Moreover, the Japanese soldiers had high individual combat skills, and often just a few of them, with limited ammunition, could hold off an entire Chinese platoon. This made the battle even more challenging, as the Japanese were not only prepared but also highly disciplined and resourceful in utilizing what they had.

Fifth Segment: From Songshan(松山) to Longling(龙陵)

After passing through Daya Kou Village (大垭口村), the road continued to ascend, and not far ahead was the Longlong Slope (滚龙坡). From the top of the slope, I had a panoramic view of Songshan (松山), Yindeng Mountain (阴登山), and Zhuzipo (竹子坡), all of which were key battlefields during the war. Following this, County Road 191 (191县道) continued southwest, eventually merging with National Highway 320 (320国道) as I approached Longling (龙陵).

Longling (龙陵) is situated in a small valley, and National Highway 320 (320国道) enters the county from the northeast. On this day, I drove 193.2 kilometers, taking 11.5 hours.

I believe that if there isn’t enough time to walk the entire length of the Sino-Myanmar Road (滇缅公路), at least the section from Baoshan (保山) to Longling should be explored. This stretch is not only rich in beautiful scenery but also dotted with numerous historical remnants from the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression.

7 Days GolfingTour

7 Days GolfingTour

8 Days Group Tour

8 Days Group Tour

8 Days Yunnan Tour

8 Days Yunnan Tour

7 Days Shangri La Hiking

7 Days Shangri La Hiking

11 Days Yunnan Tour

11 Days Yunnan Tour

6 Days Yuanyang Terraces

6 Days Yuanyang Terraces

11 Days Yunnan Tour

11 Days Yunnan Tour

8 Days South Yunnan

8 Days South Yunnan

7 Days Tea Tour

7 Days Tea Tour

8 Days Muslim Tour

8 Days Muslim Tour

12 Days Self-Driving

12 Days Self-Driving

4 Days Haba Climbing

4 Days Haba Climbing

Tiger Leaping Gorge

Tiger Leaping Gorge

Stone Forest

Stone Forest

Yunnan-Tibet

Yunnan-Tibet

Hani Rice Terraces

Hani Rice Terraces

Kunming

Kunming

Lijiang

Lijiang

Shangri-la

Shangri-la

Dali

Dali

XishuangBanna

XishuangBanna

Honghe

Honghe

Kunming

Kunming

Lijiang

Lijiang

Shangri-la

Shangri-la

Yuanyang Rice Terraces

Yuanyang Rice Terraces

Nujiang

Nujiang

XishuangBanna

XishuangBanna

Spring City Golf

Spring City Golf

Snow Mountain Golf

Snow Mountain Golf

Stone Mountain Golf

Stone Mountain Golf